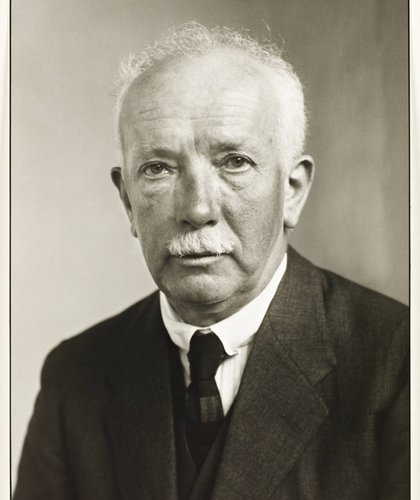

Richard Strauss

For a remarkably long time - 60 years - Richard Strauss was one of the dominant figures on the European musical scene. His talent was recognized early and carefully nurtured. His father was principal horn player in the Bavarian Court Orchestra, in Munich, and was friendly with some of the finest musicians of the day; his mother was a member of the Pschorr beer-producing family and could give her son the economic support he needed at the start of his career. By the time he was 20, his music had been performed by the likes of Hermann Levi and Hans von Bülow, two of the greatest conductors of their day. By the time he was 35, he had composed the symphonic poems Don Juan, Tod und VerklŠrung (Death and Transfiguration), Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche (Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks), Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spake Zarathustra), Don Quixote and the autobiographical Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's Life), and had become a leader of the avant-garde of European composers. He was also one of the most sought-after conductors of his day, and at various times held appointments with the Munich, Berlin and Vienna operas, as well as the Berlin Tonkünstler Orchestra and Berlin Philharmonic. Around the turn of the century, his main interest as a composer shifted from symphonic music to opera, and in the following 40 years he created such enduring works as the controversial Salome (with Oscar Wilde's lurid drama as libretto), Elektra, Der Rosenkavalier, Adriadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten and Arabella (all to libretti by the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal, with whom Strauss carried on a fascinating working correspondence, also available in English translation), Intermezzo and Capriccio. Over the years, Strauss also wrote ballets, a great deal of non-programmatic instrumental music, some choral pieces, and a large and fine body of Lieder. In 1894, he married the soprano, Pauline de Ahna. They had one son and lived a proper, bourgeois existence for the rest of their long lives. Strauss created a sort of musical portrait of the couple, his work and their domestic life in parts of several of his symphonic poems. In his dealings with the Third Reich, Strauss was obtuse and obsequious: interested only in his work, he compromised himself by treating the Nazis as if they were garden-variety politicians. His last major works, Metamorphosen, a threnody for 23 solo string instruments, and the soaring, radiant Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs), for soprano and orchestra, were written amid the destruction that the Second World War had wrought on Germany. Strauss died at his home in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, in the Bavarian Alps, at the age of 85.